Update: lockdown crime trends

Over the past few weeks I have spent a bit of time exploring police recorded crime trends before and after the UK-wide lockdown.

There has been talk of lockdowns representing the largest criminological experiment in history. Of course, determining the impact of this ‘experiment’ using police recorded crime data is not straightforward. Lots of parameters will have changed beyond people’s routine activities, amongst them, people’s ability and willingness to report crimes to the police, and policing resource allocation. It might be some time before we can fully understand how lockdowns have curbed the spatial and temporal patterns of crime.

In the meantime, open police recorded crime data can offer insight into how criminal behaviour might have changed in the past few months.

Visualising trends

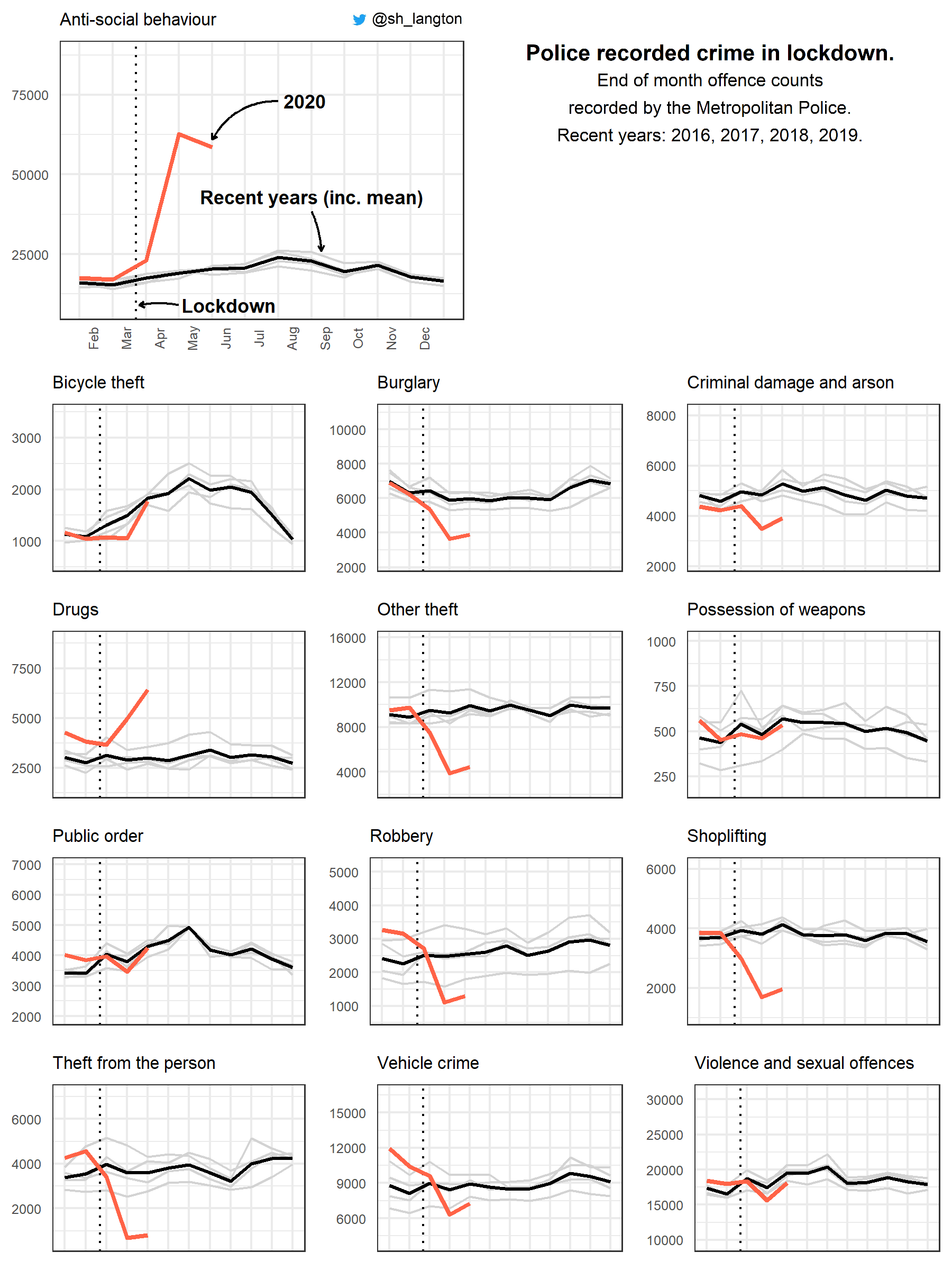

A recent article of mine explored how crime trends changed in March and April following the lockdown using London as a case study. It used a descriptive visualisation which was inspired by those used in the FT to track coronavirus deaths whilst accounting for seasonal changes in death rates. A key characteristic of long-term crime trends is seasonality. To disentangle fluctuations in crime, and try to pinpoint irregularity resulting from lockdown measures, we must account for typical monthly fluctuations. Even then, monthly data is far from ideal, but you can’t have everything (especially when working from your living room).

We now have some updated data – up to and including May, when some lockdown rules were relaxed – which demonstrates the start of a turnaround in crime trends. The code to make this visual is now available on GitHub.

The dramatic declines in burglary, robbery, theft and shoplifting observed in March and April have begun to reverse, or at least stabilise. Bicycle theft has more or less returned to normal when compared with previous years. As lockdown restrictions have eased, opportunities for crime have begun to (re)emerge. Counts are still unusually low amongst many crime types, but we are certainly witnessing a turnaround.

Given that we can attribute most ASB incidents to lockdown breaches, it is no surprise to see counts beginning to decline. It will be interesting to see where this goes in June and July. We might see a resurgence of ‘traditional’ ASB amidst a fall in incidents associated with lockdown breaches, which will complicate the picture somewhat. We will be able to disentangle this through the analysis of secure records which provide some context to incidents (e.g. text logs), but the continued closure of universities (and thus, many secure data facilities) might slow this down.

Drug activity

One of the most interesting talking points is around drugs. Initially, some reports suggested that drug use would rise during lockdown, partly due to the resultant strains on mental health. Now, there are reports that usage, at least for party drugs like ecstasy and cocaine, has declined. We might then have expected a fall in drug offences, which includes possession, consumption and/or supply. Instead, we’ve seen an unprecedented increase throughout April and May.

It is perfectly plausible that drug activity, such as those relating to ‘County Lines’, has not changed much, or declined, even amidst an increase in the number of offences being recorded by the police. Some forces reported an increase in arrests simply due to dealers sticking out on empty streets. This has been described as like shooting fish in a barrel for police, and represents a good example of how trends in police recorded crime – however useful – should be interpreted carefully.

Conclusion

The monthly release of open police crime data in the UK offers a useful on-the-fly opportunity to examine how the lockdown may have impacted on crime. I’ll be updating this visual periodically upon new data releases to see how things are changing. Please do get in contact if you have any suggestions or comments so far.

Further reads

Ashby, M. (2020). Changes in police calls for service during the early months of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic. Pre-print.

Campedelli, G. M., Aziani, A., & Favarin, S. (2020). Exploring the effect of 2019-nCoV containment policies on crime: The case of los angeles. Pre-print.

Gerell, M. (2020). Minor covid-19 association with crime in Sweden, a five week follow up. Pre-print.

Halford, E., Dixon, A., Farrell, G., Malleson, N., & Tilley, N. (2020). Crime and coronavirus: social distancing, lockdown, and the mobility elasticity of crime. Crime Science, 9(1), 1-12.

Stickle, B., & Felson, M. (2020). Crime Rates in a Pandemic: the Largest Criminological Experiment in History. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 1-12.