The universality of street segments: length and sinuosity

In recent years, a consensus has begun to emerge over the suitability of street segments for visualising and analysing the geographic patterning of crime. A number of studies have argued / demonstrated that these so-called ‘micro’ places are not only theoretically meaningful behavioural spaces, but that most action occurs among street segments. This makes them particularly useful units of analysis for studying criminal behaviour and designing crime-reducing interventions.

But how useful is the ‘street segment’ in different urban contexts? To what extent are these micro units comparable between cities, and between countries? So far, I haven’t found much data-driven research into the uniformity and ‘universality’ of street segments in terms of their physical characteristics. But to me, there are reasons to examine this issue further. In Sweden, for instance, street segments have been described as “virtually useless” because many urban areas are designed to be car-free, and consequently do not have ‘street segments’ in the same sense that other countries do.

Unfortunately for us, the UK does not have the foresight to have many car-free urban areas. However, it does contain cities with highly variable histories of urban development. It seems / seemed implausible to me that the physical characteristics of street segments in, say, Milton Keynes, a purpose-built town which did not exist until the 1960s, were comparable to those in Edinburgh, which gained city status around 400 years ago, or Birmingham, which underwent dramatic urban regeneration following extensive bombing in World War II.

To satisfy my own curiosity, and to gauge people’s interest / enthusiasm for the topic, I have spent a bit of time exploring the physical characteristics (length and sinuosity) of street segments in the UK. All the code used to generate these (very preliminary) findings is openly available. This work represents early thoughts and explorations, so if anyone has any comments or pointers, please do get in touch.

Street segments

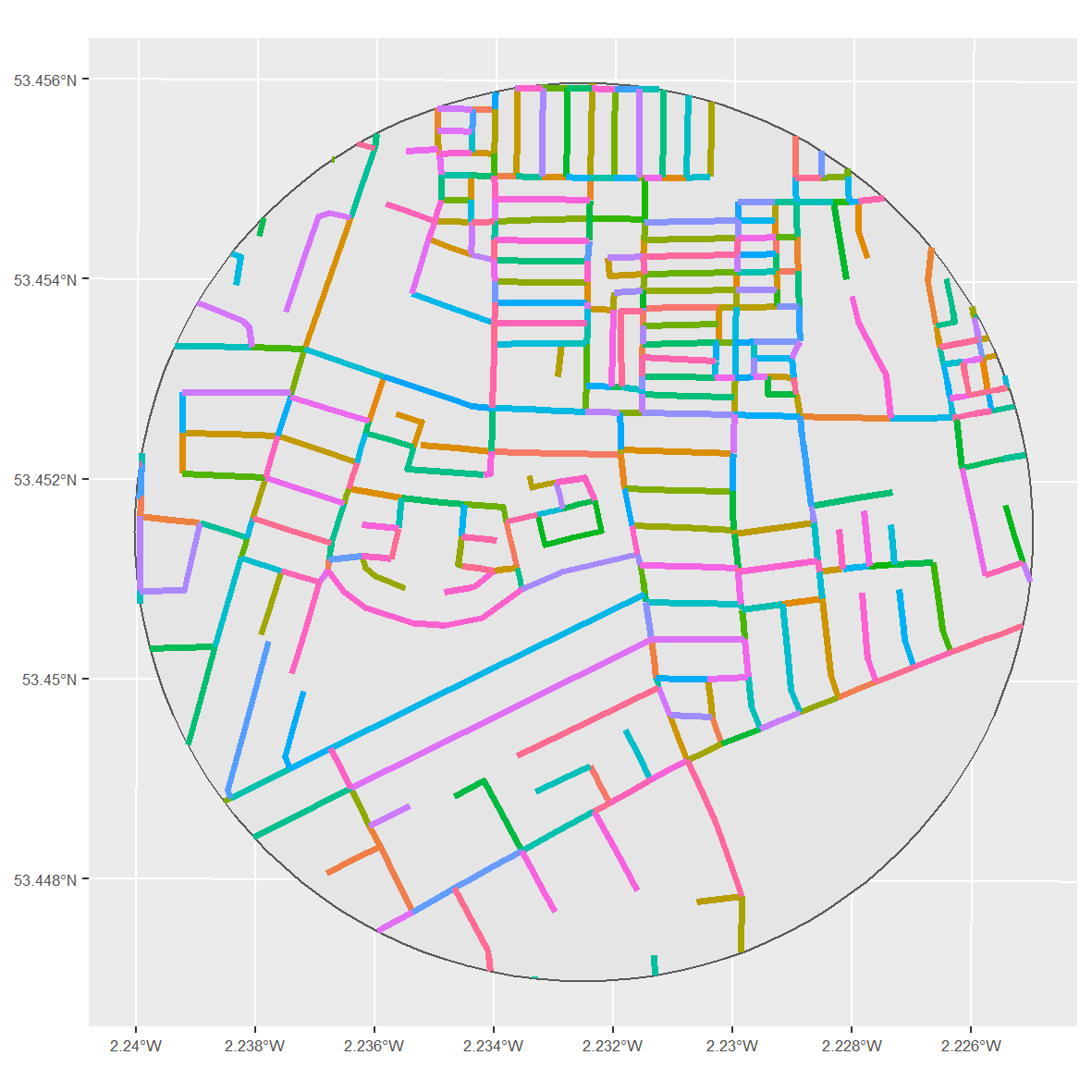

Street segments are defined as “the two block faces on both sides of the street between two intersections”. While the definition is geared towards the grid-based street networks of North America, we can apply a comparable concept to the UK using data from Ordnance Survey Open Roads. Here, individual streets are defined (and given a unique ID) based on meeting intersections. As an example, the following visual plots street segments within a 500-metre buffer in the centre of Manchester. Each road ID has been coloured to help demonstrate the individual street segments (although note that there are a limited number of colours available).

To me, the Ordnance Survey data fits the definition of street segments rather well. Each coloured line (i.e. individual ID) represents both sides of the street, and each line is segmented based on its intersection with another road.

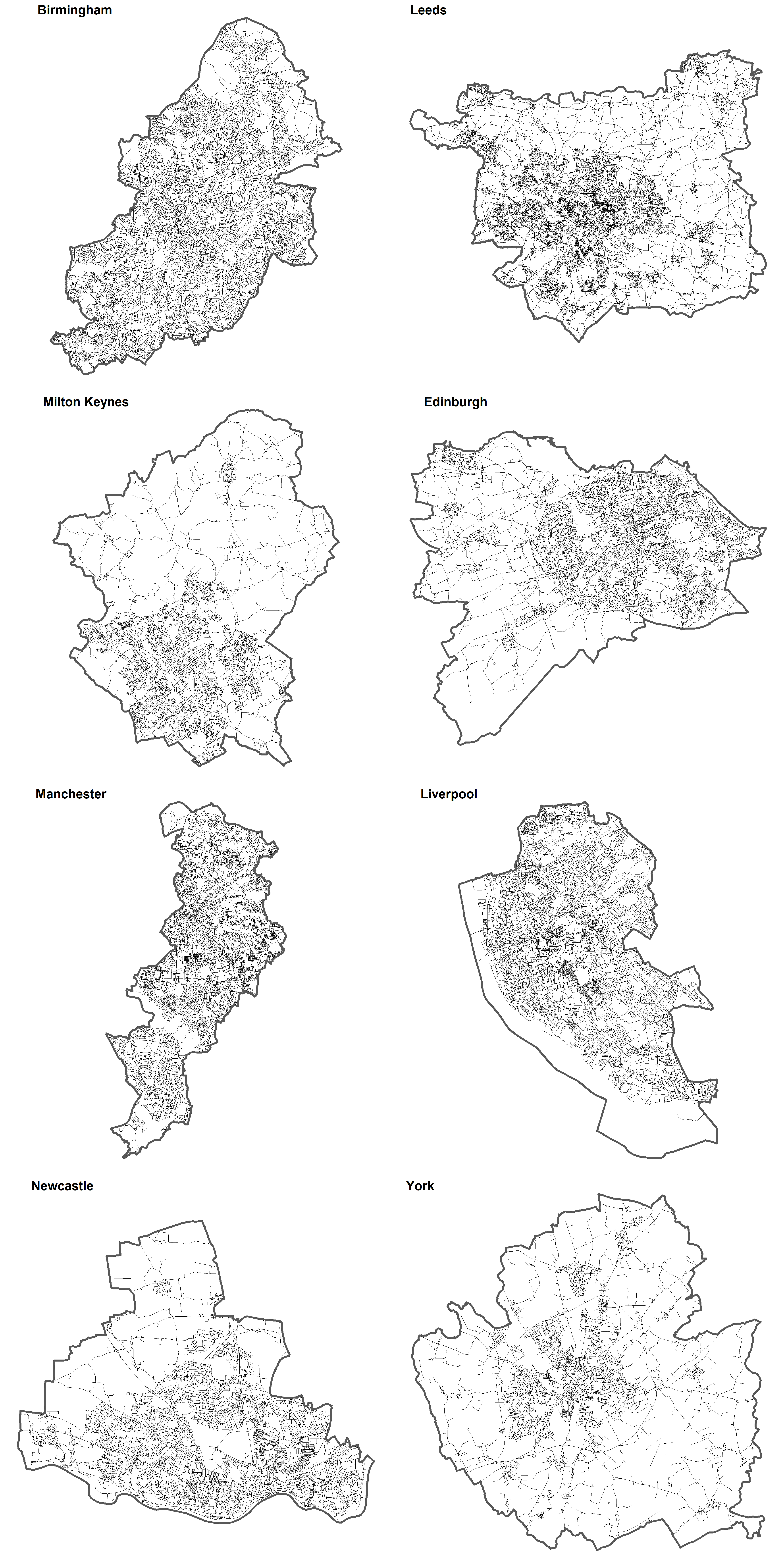

I collated this data for eight major towns and cities in the UK. Roads were clipped according to the town or city boundary (defined using the Open Street Map API – see code), and those roads classified as motorways (highways) were removed. As evidenced below, the city boundaries sometimes include satellite towns and hamlets. This raises a related discussion about the universality of street segments in terms of urban/rural areas and how city boundaries are defined – I might return to this another time.

For now, I focus on describing the physical characteristics of these street segments in two ways: length and sinuosity. By examining the degree to which street segments are homogeneous in length and sinuosity, both within and between study regions, we might shed some light on the degree to which they can be considered uniform, and in turn, ‘universal’ units of analysis.

Length is fairly self-explanatory. We are talking about it in the conventional sense (metric length) rather than other definitions (e.g. topological length). Although there is not much information out there, there appears to be at least some variation in the length of street segments used in crime concentration research. It is often added as a control variable, since longer streets might have more crime by virtue of their length, rather than whatever we are interested in.

But would excessive ranges (maximum - minimum) and variation in street segment length undermine the idea that street segments are a universally useful micro unit of analysis? Can we confidently compare study regions which are comprised of street segments with drastically different length characteristics (e.g. mean, variation, minimum, maximum)?

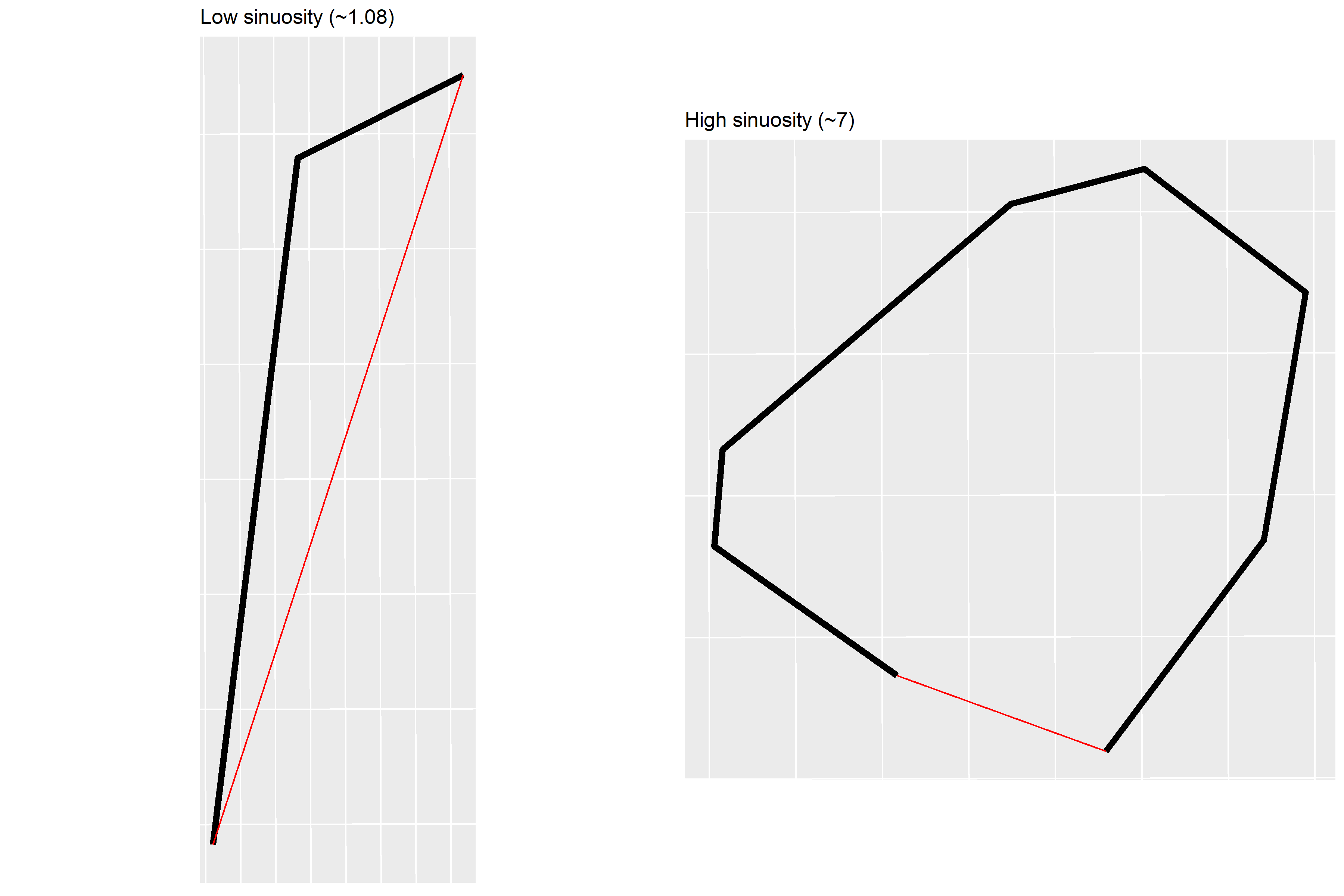

Sinuosity is a fairly new concept to me. In crude terms, and at the risk of annoying geographers and mathematicians, sinuosity in this context represents a measure of ‘straightness’. It is calculated by dividing the actual length of a line by the straight line distance (i.e. the distance between the start and end point). So, a perfectly straight street segment, for which the actual length and straight line length are the same, will have a sinuosity of 1, the smallest value possible. The example below, using street segments randomly sampled from Birmingham, demonstrates this concept. The black line represents the raw street segment, and the red line is the shortest distance from start to finish.

Again, the reasoning behind examining sinuosity is to scrutinise the universality of street segments as meaningful behavioural spaces to study crime. A huge amount of variation in the sinuosity of street segments (either within the same study region, or between different study regions) might give reason to question this. Modern, grid-based cities might be almost entirely comprised of street segments with a sinuosity of 1. Cities with a long and convoluted history of urban development might have far more irregularity or quirks (e.g. right figure above). In which case, would the definition of ‘street segment’ generate units of analysis which still hold the same theoretical meaning?

Characteristics

For now, I have generated a series of descriptive statistics to try and summarise the length and sinuosity of the eight study regions. On top of statistics on raw length (e.g. ‘Mean length’) and sinuosity (e.g. ‘Mean sin.’) for each study region, I have calculated the proportion of street segments which are straight (‘Prop. straight’). This is simply the proportion of streets with a sinuosity of 1 (when rounded to six decimal places).

The figures on length alone generate some interesting discussion. The maximum lengths, which range from around 1200 metres to nearly 3600 metres, are clearly dragging the mean up. Recall that we removed motorways, but not A-roads or B-roads, which can be quite long. That said, A and B-roads are common even in dense urban areas, and contain plenty of opportunities for crime (e.g. petrol stations, residential dwellings). Removing them would come at a cost. The median might prove more useful. Quite a few study regions have a median street segment length of ~60 metres, but for instance, Edinburgh is noticeably longer (~72 metres) and Manchester a little shorter (~53 metres).

The minimum values are amusingly small – perhaps showcasing some quirk in how the Ordnance Survey generate segments (e.g. roundabouts, which in previous research required additional data handling).

| City | Mean length (metres) | Median length (metres) | SD length (metres) | Min. length (metres) | Max. length (metres) | Mean sin. | Median sin. | SD sin. | Min. sin. | Max. sin. | Prop. straight |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birmingham | 91.29 | 69.28 | 83.48 | 0.01 | 3573.64 | 1.05 | 1 | 0.30 | 1 | 26.13 | 0.60 |

| Leeds | 90.32 | 62.62 | 111.75 | 0.01 | 2716.05 | 1.05 | 1 | 0.32 | 1 | 30.39 | 0.62 |

| M. Keynes | 96.94 | 61.80 | 137.50 | 0.03 | 3489.49 | 1.08 | 1 | 1.81 | 1 | 219.30 | 0.48 |

| Edinburgh | 102.59 | 72.44 | 126.60 | 0.11 | 3116.51 | 1.07 | 1 | 0.34 | 1 | 16.53 | 0.57 |

| Manchester | 68.02 | 53.40 | 59.50 | 0.02 | 1227.02 | 1.07 | 1 | 4.04 | 1 | 632.77 | 0.74 |

| Liverpool | 81.10 | 60.42 | 72.65 | 0.03 | 1557.76 | 1.05 | 1 | 0.32 | 1 | 28.99 | 0.68 |

| Newcastle | 85.51 | 61.00 | 95.72 | 0.13 | 3010.29 | 1.07 | 1 | 0.46 | 1 | 29.08 | 0.64 |

| York | 111.76 | 69.35 | 159.06 | 0.10 | 3442.73 | 1.06 | 1 | 0.25 | 1 | 8.66 | 0.58 |

How do these UK cities compare to elsewhere? One study from The Hague (the Netherlands) reported a mean length of 94 metres and a standard deviation of 108 metres. This makes it fairly similar to Leeds, for instance. A study in Boston (United States) reported a mean of 130 metres, although no standard deviation was mentioned. The minimum length in that study was ~3 metres, and maximum ~640 metres. Another in Brooklyn Park (United States) had a mean length of 182 metres. This is considerably different to say, Manchester (Mean = 68 metres, Median = 53 metres), and strikes me as quite important when it comes to treating street segments as a universal micro unit of analysis.

What about sinuosity? Generally speaking, it appears that street segments are fairly straight. The median sinuosity across all study regions is 1. Mean sinuosity is fairly low (but similar to the left example above – which isn’t exactly straight), although this may be dragged up by outliers, such as in Manchester.

The proportion of street segments which are straight (sinuosity = 1, to nearest six decimal places) is quite high, but varies quite considerably between cities. In Milton Keynes, only 48% of street segments are straight, whereas this figure is 74% in Manchester. If you had asked me beforehand, I would have guessed that Milton Keynes would have had the highest percentage out of all the study regions, due to its unusual (for the UK) grid system. The surprise might result from the study region boundaries, which for Milton Keynes included villages and hamlets outside of the main town centre. Note that it still has a median sinuosity of 1 due to rounding.

Conclusion

This has been a very preliminary investigation into the homogeneity of street segments in terms of length and sinuosity. The idea is / was that street segments should have reasonably homogeneous physical characteristics if we want to consider them to be ‘universal’ micro-level units of analysis in crime concentration research, and represent comparable behavioural spaces to study crime.

To me, findings certainly suggest that it is worth investigating this topic further. The length of street segments appears to vary quite considerably between study regions – both those presented here, and those in existing research. These differences may well narrow with further data handling, for instance, the removal of outliers or specific features such as a roundabouts. However, in that case, we might consider (1) outlining how and why street segments were kept/removed from analysis in a manner which is systematic and transparent, (2) demonstrating or discussing the implications of keeping/removing street segments, and/or (3) refining the definition of street segment to exclude those roads which are far too short or long to be reasonably comparable.

In terms of sinuosity, I have been surprised to see that many street segments in these UK study regions are more or less straight. However, the degree to which this holds true varies between study regions. Outliers with exceptionally high sinuosity might prove problematic in terms of keeping micro units of analysis uniform and comparable. In which case, the same three points above would apply regarding transparency, implications and definitions.

Next steps might be:

- Perform some further data handling on the Ordnance Survey data to establish whether some systematic rules can create study regions with uniform street segments in terms of length and sinuosity.

- Explore the implications of the above for crime analysis.

- Explore alternative definitions of street segments (e.g. segment roads based on angle change between nodes, rather than intersections alone).

- Examine other physical characteristics (e.g. width).

- International comparisons.

Further reading

Buil-Gil, D., Moretti, A., & Langton, S. (2020). The integrity of crime statistics: Assessing the impact of police data bias on crime mapping. Pre-print.

Steenbeek, W., & Weisburd, D. (2016). Where the action is in crime? An examination of variability of crime across different spatial units in The Hague, 2001–2009. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 32(3), 449-469.

Taylor, R. B. (2015). Community criminology: Fundamentals of spatial and temporal scaling, ecological indicators, and selectivity bias (Vol. 12). NYU Press.

Weisburd, D., Groff, E. R., & Yang, S. M. (2012). The criminology of place: Street segments and our understanding of the crime problem. Oxford University Press.